You hold me in your hands while you dream. It is not just my beauty you drink in with your eyes, nor is it merely the craftsmanship of the hands that fashioned my beads and strung them on silk that delights you.

It is also the sound of the music I make: mystic melodies of the sea

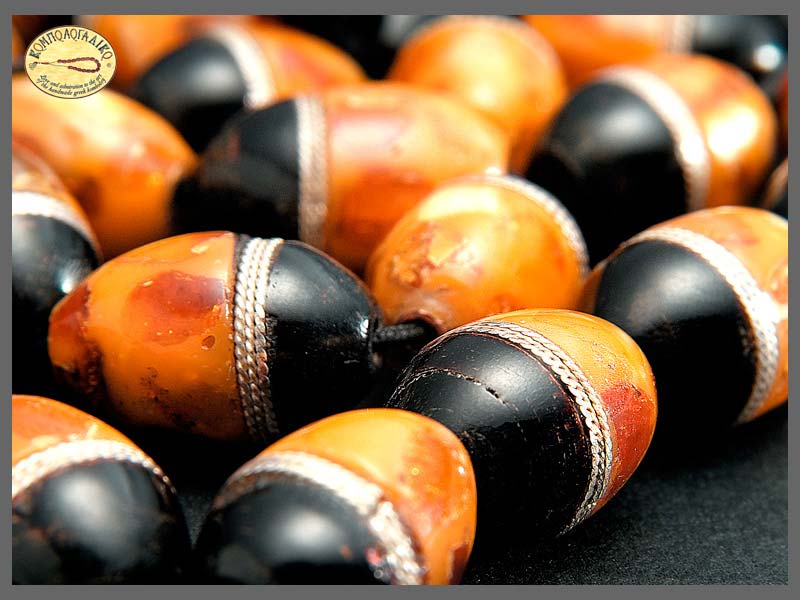

from my coral beads, or the whisper of amber, permeated by the aura and aroma of ancient forests where resins fossilized... The rhythmic sounds of stones from far-off lands are the song that now keeps you company.

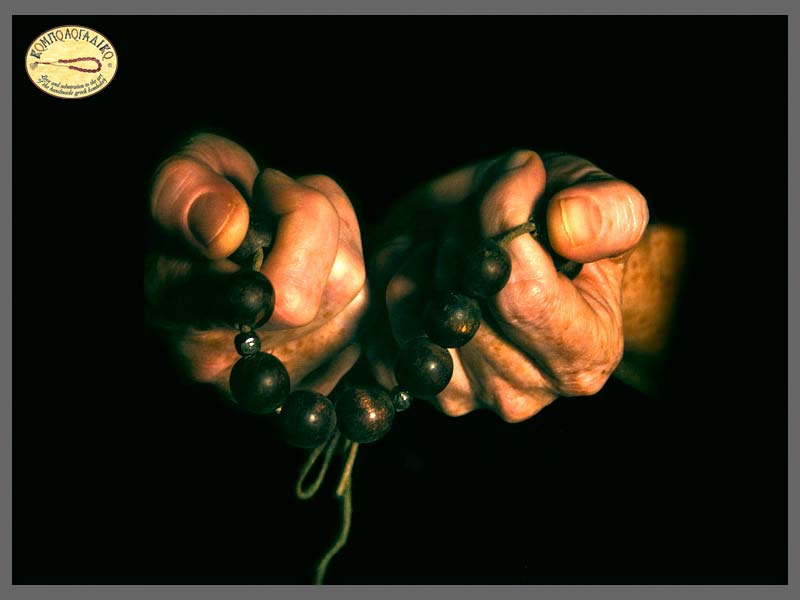

Taking warmth from the palm of your hand, I slip tenderly between your fingers, sweetening the passage of time. A tangible presence in your solitude, I am present in moments of happiness as well as sadness. When you are anxious, I bring patience. When you are troubled, I bring calm. When you are revelling, I am your companion. When you are longing from desires unfulfilled, I am your solace.

I am a work of art and soulful friend in one. Something precious, yet commonplace at the same time... You have said on occasion that I am your heart’s desire, your passion. But more than this, the way we have bonded, you and I, I have become an extension of yourself – a part of your very soul.

In the first instance, the odd-beaded komboloi is said to nestle better in the palm of one’s hand, creating an elegant ‘garland’ whose circle closes with a single bead. In addition, the other beads are ‘played’ more easily in pairs which glide downward rhythmically and melodically in a more balanced progression when they terminate at the single bead which defines their way. And, finally, for the komboloi to bring good luck, it’s beads must be odd in number... simply because tradition says so.

The standard number of beads of a komboloi is 33 which some people believe signifies the number of years Jesus lived on earth. Others maintain that the number corresponds to the first knotted string for prayer associated with the monk Pahomiou (whom we will encounter again in due course). There is also a third version which relates that the komboloi originates in the Muslim tradition in which prayer beads originally numbered 99. Mohamed is said to have commended the faithful to hold 99 beads in order to assist them in recalling the 99 names or attributes of Allah. This string was called a Masbaha, meaning 'to recite prayers’. By way of abbreviation, the number 99 was divided by 3, so that the standard string now comprises 33 beads. This number has prevailed for practical reasons and thus each larger bead ‘counts’ for three of Allah’s attributes. Greeks refer to this larger bead as the papas which for the Muslims represents Allah himself.

As the komboloi evolved during the years of Turkish occupation, the number 33 was no longer observed and the Greeks reduced the number of beads to 23. It is believed that this change may have been a reaction against Ottoman control thus embodying a symbolic form of resistance. No one is certain what prompted this change, but we may be confident that, for the Greeks, the beads of the komboloi did not signify the names of Allah. Moreover the Muslim Masbaha's beads are tightly strung together and are stationary. In its Greek manifestation, several of the beads have been removed to permit them to flow freely and thus allow for the enjoyment of their delicate play and subtle music.

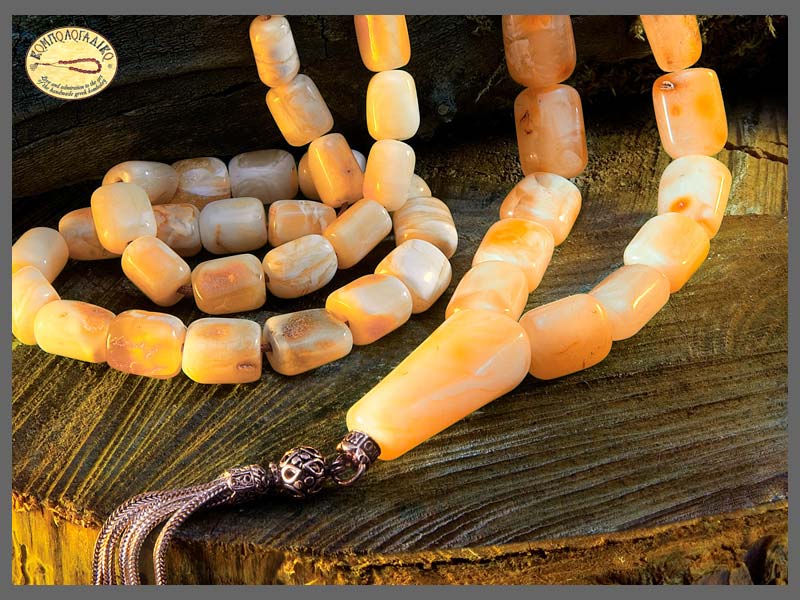

Komboloi beads should be strung on a cord, preferably made of silk. Today it is common to find beads on metal chains, but enthusiasts believe this is merely a passing trend. Chains are considered categorically unorthodox as it deprives the komboloi of its traditional authenticity and has the added disadvantage of wearing the beads away by ‘filing’ them down with use.

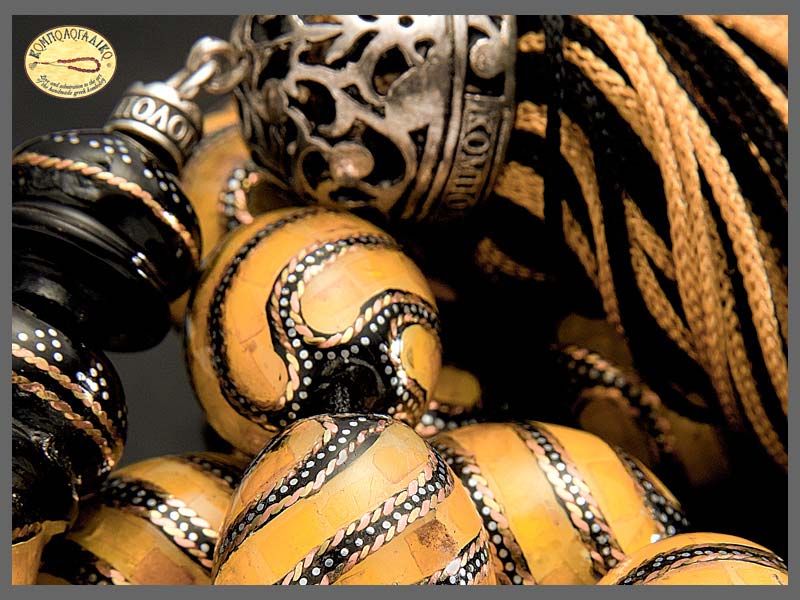

In addition to the requisite silk cord, other characteristic features of the komboloi are the papas and the founda. The papas (which literally means 'priest' in Greek) is the single bead that is larger than the rest whose style is often altogether different from the others. Its place is at the end of the loop where the ends are joined together.

The founda is the tassel tied to the end of the string behind the papas. Devotees believe that much of a komboloi's charm is in its founda. The simple tassel is soft and silky and plays an important role as a stress reliever. Although it is a simple embellishment, it is impossible to think of the traditional komboloi without it. In bygone days the founda was rich and dense. The work of the tassel maker was so revered that it was considered not merely a profession, but an art form in its own right. Stroking the founda evokes a sweet serenity in the depths of your heart.

Today, however, it is common to find modern komboloi without the founda. It seems younger generations consider it old-fashioned while 'traditionalists’ believe that a komboloi without a founda is shamefully incomplete and disfigured. The so called koutsavakides2 were partly responsible for the disappearance of the founda as silk was expensive. They also began omitting the larger, costlier papas and reduced the number of beads to 17.

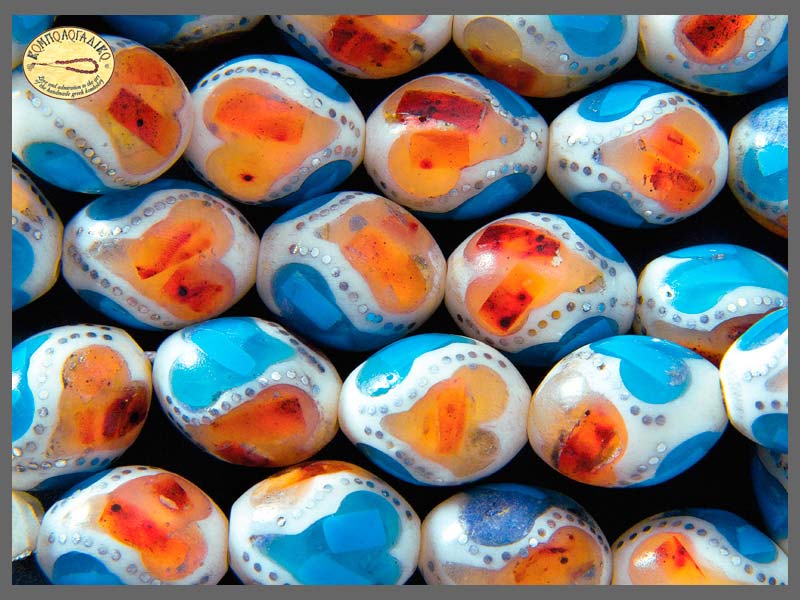

Anthimou Gazi's Greek dictionary published in Athens in 1839 sites an interesting verb: kombeo-kombo. The verb is defined as: ‘sound, ringing, especially sound emanating from terracotta or metal objects when one collides with another’. If one assumed that the affinity between the words kombeitai and komboloi is a coincidence and that the sound – kombos – the beads make ‘when one collides with another’ is not one of its fundamental elements, one would, indeed, be mistaken.

It is, in fact, no coincidence at all because the komboloi is also music... Literally and metaphorically, as Elias Petropoulos3 writes in his book Rebetika Tragoudia:4 ‘the komboloi is also an accompaniment to the baglama.5 The musician held his komboloi from its tassel in his left hand which hung from a button hole of his clothing while he tapped the beads rhythmically against his wine glass’. Some old-school folk singers may still be observed in this practice.

The sound of the komboloi is its voice. ‘Don’t bang the beads’ as the well-known folk song says, but not for the reasons implied in the lyrics6. Rather it is because beads are made of stone, amber, coral, bone, horn, ebony, etc., and one must play them gently and quietly in order really to be able to hear what they are saying.

The soul of the komboloi – its voice – is the music of its beads, whatever their shape, whether flat or irregular, translucent or opaque, made of stone, gems, wood, amber, bone, or even from olive pits, or carob beans.

Antiquated encyclopaedias identify beads as: [a small object] ‘perforated at its spherical axis for threading’... Quite a mundane definition for something so rich and intriguing an artistic creation with so much symbolism and history!

It seems humankind has used beads since prehistoric times. Early civilizations believed they were a charm against enemies, or illness, or even the capricious catastrophes of nature. Evidence of their early use can be found in the bead-laden masks of the indigenous peoples of Mali, Congo and Cameroon. Here the humble ‘perforated spheres’ were seen as having supernatural powers.

Charm or adornment, science or superstition, through the ages beads have been used for religious, aesthetic and practical purposes.

One example of its practical use began in ancient Chinese where they first used the abacus and gave it didactic significance. It was also known in Greece from ancient times and was still in use during the Turkish occupation. The avax, as it was called, was an upright fixture composed of taut metal chords with gliding circular wooden beads. Each bead could represent either a single number or tens or hundreds. The avax was used both for performing calculations and also for teaching children the basic concepts of arithmetic.

A modern Greek distortion of this ancient word is abaco. If someone was considered exceptionally learned, a demotic expression reflecting this wide knowledge referred to them as ‘knowing the abaco’ – signifying a ‘great deal’. By extension today, it is still common to say someone has ‘eaten the abaco’ if he has eaten too much.

Back in the day, Spyros Zagoraios sang ‘Sevdas lipon kai to begleri...’9 which can be interpreted to mean the begleri offers one comfort when suffering from unrequited love...

The begleri is not a komboloi in the true sense of the word, i.e. a string of beads forming a closed circle, but rather is open-ended with beads positioned symmetrically in pairs on either side of the cord without the odd bead in the middle characteristic the classic komboloi. The string is a straight line with only a few beads, typically 6 or 8. The ends are often sealed with silver caps.

The youth of today often prefer the begleri to the komboloi. The simplicity of its design, its length and width (which are much smaller by comparison) make it more appealing. Not to mention it is easier to carry in the more slim-fitting pockets of blue jeans or summery shirt pockets. It is less ‘demanding’ and thus makes a fine little companion.

When we are feeling anxious or lonely, nothing soothes the soul more than touch for, more than any of the other senses, it is capable of bringing the most comfort and consolation. With a soft caress, a firm squeeze of the hand, or a warm embrace, we find the affection, companionship, and refuge we seek.

The komboloi has a reassuring feel... a tangible, encouraging presence. At times when we are worried or confused, or when we are plagued by vexing thoughts that make us irritable, it can put our minds at ease. Although devotees have made many laudable claims about the komboloi, it is not an exaggeration to say that it has a calming effect that provides balm for the spirit in distressing times. Moreover, in accord with acupuncture principles, it is also alleged that handling the beads stimulates areas of the fingertips which induce well-being. Thus, even beyond its psychological benefits, the komboloi offers a palpable sense of serenity as well.

India 700 BCE until today

Historically the komboloi was associated with prayer. The Hindus were the first to string beads together and use them for counting prayers which they called mala. The beads were made from the seeds of a tree that, according to tradition, only grew in Java. They were hard and rough to the touch and scored with five symbols repre-senting the five mani-festations of the god Shiva. They also symbolized the difficult life the faithful are obliged to live.

As a branch of Hinduism, Buddhism main-tained the tradition of mala using seeds from a tree that we often find in front of Buddhist temples and monasteries known as the sacred bodhi tree, (ficus religiosa) which means 'enlightenment’ in Hindi.

Prayer beads passed from India to China, Korea, and Tibet. The Tibetans did not limit themselves to humble seeds, but began using a wide range of material for making beads. After the spread of Buddhism in about 800 BCE, they began making their own type of prayer beads out of coral, shells, ivory, amber, turquoise and various stones and even bones. The most prized beads were made out of the bones of their saints, holy men or lamas.

The Holy Number 108

Buddhist prayer beads usually consist of 108 beads. According to tradition, the founder of Buddhism, Sakyamuni, taught king Vaidunya to thread 108 seeds of the Bodhi tree on a string and commanded him to repeat ‘glory to Buddha, the Law and the flock’ 2,000 times a day, using his string of seeds to keep count.

Another story relates that the tradition originated around 500 BCE when a Buddhist spiritual teacher developed the string of beads to assist a student who was having trouble keeping count of his prayers which he was supposed to say 108 times. The teacher’s solution to the problem was to bore holes through 108 seeds and thread them on a string, joining the ends together to keep from losing them. The number 108 represents the number of sinful desires which every Buddhist must overcome in order to reach Nirvana.

Clay from Mecca and Medina

The Koran describes Mecca as ill-suited for settlement because of drought, yet this ‘valley without vegetation’ is said to have been inhabited by Abraham, Hagar and their son Ishmael and it was here that Muhammad was born in 570 AD. After an eventful life, he died in Medina in 632. Thus Mecca and Medina became the two holy cities of Islam. When Arab travellers brought the tradition of prayer beads from India to the Islamic world, it was considered appropriate that they be made of clay from one of these two sacred places.

It was only later that wood and precious stones began to be used. Tradition dictates that there should be 99 beads which are called subha, meaning ‘praise’ with the 100th bead being the largest, (later becoming the papas in Greece), signifying the end of one prayer cycle upon which the faithful pronounce the name ‘Allah’. From this bead falls a tassel which is our well known founda. The Arabs added the tassel because they believed that evil spirits are afraid of things that sway back and forth, therefore, the tassel protects them from harm.

Part of Medieval History

Gertrude of Nivelles was the daughter of Pepin I of Landen, and an ancestor of Charlemagne. When she was 14 she entered a convent in the Belgian city of the same name built by her mother and eventually served as abbess there until her death in 659. Her tomb was destroyed by German bombing in 1940, and thus her body was discovered with a string of prayer beads. This is evidence that ‘rosaries’, as they came to be called, were already part of Roman Catholic tradition as far back as the 7th century.

It is unknown who first introduced prayer beads to the Catholic Church, but we do know that Pope Pius V, pontiff from 1566 until his death in 1572, declared that the ‘inventor’ of rosaries was St. Dominic (1170-1231), founder of the Order of the Dominicans. Thus the official introduction of the rosary goes back at least to the 12th century.

It was also designated that the beads should be made from simple materials and that the likes of coral, amber and quartz were forbidden because they were considered too luxurious.

The Order of Rosary

The Dominicans monks belted their waists with a long string of 150 beads, with dividing markers every fiftieth. The rosary was considered to be a spiritual inspiration and an empowerment of faith. As they went from country to country throughout Europe, people began to refer to the Dominicans as the ‘Order of the Rosary’ because of the string of beads they wore.

Images of Greece

In Greece, there is a very strong link between humanity and worry beads. They are a pervasive element of society and an important part of folk tradition. In the summer it is a common sight in the cafés in the shade of the plane trees, while in the midst of winter it is a natural companion clicking away in the hands of someone warming themselves by a wood-burning stove, or in the little deli off the village square with bit of raki.

These are all images of Greek life in which the komboloi is at home; scenes of both past and present, documenting a timeless relationship that not only survives, but grows stronger with the passage of time. But the tradition of worry beads is much deeper than this and more than the simplistic popular song lyrics denotes: ‘I whiled away my time with you’16, for it is not simply a common and mundane way to combat boredom; it is many things, including a good luck charm and talisman. The old mule-drivers used to hang beads, usually blue, on the heads of their horses or donkeys. Now we see them hanging from tractors and cars. The history of beads in Greece is really a love story... but how did it start?

Orthodox prayer beads: the Komboskini

It seems the first place in Greece known to have used ‘beads’ was the monastic community of Mount Athos where monks tied knots at intervals on a thick cord to count their prayers. These ‘knotted strings’ known as komboskini were used for counting prayers and opened the road for the Greek komboloi, or worry beads.

The origins of the komboskini are rather obscure, but one monk claims it began with saint Pahomios, who was once an idolater and who had fought as a soldier in Roman Egypt during the 3rd century. He eventually became an ascetic and built his cell near the Nile River, latter organizing a community of over 3,000 monks. It is alleged that they often lost count of the number of prayers they were reciting and one night the Archangel Gabriel visited the saint in a dream carrying a silk cord and taught Pahomios how to count prayers. He tied knots in the cord each one woven from 9 crisscrosses representing the orders of the angels. After making 33 knots he tied the ends of the cord together and this is alleged to be the origin of prayer beads or komboskini. Orthodox prayer beads are usually made from black sheep's wool, symbolic of the Lamb of God and are not always made of 33 knots but vary according to the prayers the monk wishes to recite. They can number 50, 100 or 300 accordingly.

From the Komboskini to the Komboloi

Greece is the only place where the tradition of using beads for prayer is no longer relevant and the beloved komboloi has become an object purely of secular pleasure without any residual religious connotations.

This change came about during the long period of Ottoman occupation when the Turks of Greece held in their hands a tespich which was Hellenized to become a despigi. The Ottoman tespich had beads with no space between beads to allow them to glide along the string since its purpose was only to count prayers.

In other words, it was a garland of motionless beads which the Turks held not only at prayer time but also during formal occasions and celebrations. The Greeks inherited the garland of beads from the Turks, but they adopted it with a much more playful disposition. One per-spective maintains that their use of the beads was intended to mock their oppressors, while another holds that, paradoxically, it was meant to keep their hands ‘busy’ so as not to be led astray. Another theory holds it was intended to deter the custom of shaking hands which the Turks forbade.

Thus, on the enslaved mainland, in Evia and the Peloponnese the Turkish tespich transformed into the worry beads of the raya or the ‘enslaved ones’... With a resolute spirit and ingenuity, the Greeks removed many of the beads from the string, to create spaces between the beads so they could play more freely. Thus the komboloi became an animated living being that sings and sighs.

During the Period of King Otto

The pyrpolitis,17 now in his 60th year, donned European clothing, and was wearing a tail-coat. His hair was white and cut short and he had a thick moustache. In his large reddish hands he clicked away at a black ebony komboloi. Thus the French writer and photographer Maxime Du Camps describes Constantine Kanaris18 whom he visited in 1850 in Athens as recorded in his literary reflections translated by Babis Anninou. In the newly liberated Greek state under King Otto, the komboloi had not yet encountered the period of decline it was later to see in the early 20th century. During this era, it was in the hands of every man of prestige.

In the newly liberated Greek state under King Otto, the komboloi had not yet encountered the period of decline it was later to see in the early 20th century. During this era, it was in the hands of every man of prestige.

A Stroll through the Neighborhood of Psirri Back in the Day

The Koutsavakides were largely responsible for the demise of the komboloi namely because it acquired a negative image which was associated with these lawless and audacious figures. Their komboloi was made of common, even base materials. But let us go back in time with Timo Moraitini and Dimitris Skouze as our ‘guides’ to become better acquainted with the Koutsavakides, who they were and what they represented...

But before we turn to them, let us go back even further in history to the period immediately after the war of independence when the freedom fighters of the glorious revolution of 1821 found themselves out of action. Those who were still alive would frequent a cafe off the main square in the Psirri neighbourhood in central Athens which the Athenians named the ‘Square of Heroes’ in their honour.

The komboloi of humanity,

which fulfils men’s needs,

brings happiness for he who holds it,

and honour to its beads.

–Cretan mandinada

For decades the komboloi fell from favour and was even regarded with disdain because of the bad image it got from its association with the Koutsavakides. The characters in Karagiozis shadow puppet theatre reinforced this negative image - for who among the shadow theatre characters had a komboloi but uncle George, the naive, illiterate, uncouth character who would come to town laden with cheeses and crates of milk, or the liar and braggart Stavrakas, who was perpetually unemployed and could be thought of as a genuine Koutsavaki, frequenting various dens of pleasure getting into mischief...

Those Who came from Across the Way

It appears that this attitude towards the komboloi began to change after the1920s with the coming of the refugees from Asia Minor ‘catastrophe’21. According to the decedents of refugees, they were the first to begin to make and sell the genuinely Greek komboloi.

The journalist and author Katerina Agrafiotis interviewed many of the grand-children of these first refugees and recorded their memoirs. One such recollection told of their family moving to the down-trodden suburb of the port of Piraeus known as Kokkinia where they built a makeshift house. Having brought with them a machine from ‘across the way’ they began to manufacture commercial beads and komboloi. Soon they were able to open up shop in downtown Piraeus, being one of the first to set up a business selling komboloi. Thus there was a new impetus promoting Greek worry beads, making it once again acceptable in the everyday lives of people of all classes.

The End of the War

During the interwar period the upper classes continued to guard against the reintroduction of the komboloi – a stance which was soon to be subverted. The sweeping change brought about by the Second World War was to prove a great catalyst on all levels, forcing people to re-evaluate many of their long held perspectives.

The much disparaged komboloi becomes, once again acceptable, and after 1945 the growing number of devotees who found solace in its company no longer felt guilty about their affection. The war was over. The years that followed saw the reputation and status of the komboloi re-established, with initiates, and converts, discovering and adopting it anew. People began collecting and exhibiting worry beads with enthusiasm as it became part of their circles of friends, given as a gift of camaraderie.